This is a follow-on from my article introducing algebraic data types and explaining how to implement them in Raku. If you are not familiar with algebraic data types, I suggest you read that article first. In this article I use algebraic data types to create a statically typed version of a list-based parser combinators library which I originally created for dynamic languages. The article introduces list-based parser combinators are and how to implement them in Raku and Haskell using algebraic data types.

Perl, Haskell and Raku: a quick introduction

The code examples in this article are written in Perl, Haskell and Raku. If you are familiar with these languages, you can skip this section. The code is written in a functional style and is not very idiomatic so you should be able to understand it easily if you know another programming language.

Perl and Raku are syntactically similar to C/C++, Java and JavaScript: block-based, with statements separated by semicolons, blocks demarcated by braces, and argument lists in parentheses and separated by commas. The main feature that sets Perl and Raku apart is the use of sigils (‘funny characters’) which identify the type of a variable: $ for a scalar, @ for an array, % for a hash (map) and & for a subroutine. Variables also have keywords to identify their scope, I will only use my which marks the variable as lexically scoped. A subroutine is declared with the sub keyword, and subroutines can be named or anonymous:

sub square ($x) {

$x*$x;

}

# anonymous subroutine

my $anon_square = sub ($x) {

$x*$x;

}

Haskell is whitespace-sensitive like Python, but has a markedly different syntax. Because everything is a function, there is no keyword to mark a function; because there is only lexical scope, there is no need for any special scope identifiers. Function arguments are separated by spaces; anonymous functions have a special syntax to identify them:

-- named function

square x = x*x

-- lambda function bound to a named variable

anon_square = \x -> x*x

Several of the examples use the let ... in ... construct, which behaves as a lexically scoped block:

let_square x a b c = let

x2 = a*x*x

x1 = b*x

x0 = c

in

x2+x1+x0

x0, x1 and x2 are in scope only in the expression after the in keyword.

Haskell is statically typed, and the type of a function or variable is written in a separate annotation, for example:

isEmpty :: [a] -> Bool

isEmpty lst = length lst == 0

The isEmpty function has a type signature, identified by ::, that reads “isEmpty is a function from a list of anything to a Boolean”. Types must be written with an initial capital. The a is a type variable which can take on any type, as explained in my previous post.

Raku has optional typing: you can add type information as part of the declarations, for example:

sub isOfSz(@lst, Int $sz --> Bool) {

@lst.elems == $sz;

}

This function takes array of any type and an integer and returns a Boolean.

Other specific bits of syntax or functionality will be explained for the particular examples.

Parsers and parser combinators

What I call a parser here is technically a combination of a lexer or tokeniser and a parser. The lexical analysis (splitting a sequence of characters into a sequence of tokens, strings with an identified meaning) meaning and parsing (syntactic analysis, analysing the sequence of tokens in terms of a formal grammar) are not separate stages.

Parser combinators are building blocks to create parsers by combining small parsers into very complex ones. In Haskell they became popular because of the Parsec library. This library provides monadic parser combinators. My parser combinator library implements a subset of Parsec’s functionality. I am not going to explain what monads are because the point of creating list-based parser combinators is precisely that they do not require monads. There is a connection however, and you can read about it in my paper if you’re interested.

I created the original version of the list-based parser combinators library for dynamically typed languages: there are versions in Perl, Python and LiveScript, a Haskell-like language which compiles to JavaScript.

Because I like Raku and it has gradual typing, I was interested in what a statically typed Raku version would look like. As a little detour I first implemented them in Haskell, just for fun really.

Raku has Grammars, which also let you build powerful parsers. If you are familiar with them it will be interesting to compare the parser combinator approach to the inheritance mechanism used to compose Grammars.

List-based parser combinators

So what are list-based parser combinators? Let’s say I want to parse a string containing this very simple bit of code:

assignStr = " answer = 42"

We have an identifier, an assignment operator and a natural number, maybe preceded by whitespace, and with some whitespace that doesn’t matter between these tokens. I am assuming that the string which we want to parse is code written in a language which is whitespace-insensitive. What I would like is that I can write a parser for as close as possible to the following:

assignParser = [

maybe whiteSpace,

identifier,

symbol "=",

natural]

And when I apply assignParser to assignStr, it should return the parsed tokens, a status, and the remainder of the string, if any. So each parser takes a string and returns this triplet of values (I’ll call it a tuple instead of a triplet). We’ll define this more formally in the next sections.

What we have here is that the list acts as the sequencing combinator for the specific parsers. The maybe is a combinator to make the token optional. We can provide more combinators, such as choice, (to try several parsers), many (to repeatedly apply a parser), etc. And because every parser is a function, complex parsers can easily be composed of smaller parsers expressed in terms of the building blocks. For example, if we had many assignments, we could have something like

assignsParser = many assignParser

Now suppose that we want to extend our parser to include declarations, something like

" int answer"

which we parse as

declParser = [maybe whiteSpace, identifier, identifier]

then we need to add get the following parser:

statementsParser = many (choice [assignParser,declParser])

It is also essential that we can label tokens or groups of tokens, so that we can easily extract the relevant information from a parse tree, as the intermediate step in transforming the parse tree into an abstract syntax tree. In the above example, we are only interested in the variable name and the value. The whitespace and equal sign are not important. So we could label the relevant tokens, for example:

assignParser = [

whiteSpace,

{"var" => identifier},

symbol "=",

{"val" => natural}

]

Implementation in a dynamically typed language

How do we implement the above mechanism in a dynamically typed language? A parser like identifier is simply a function which takes a string and returns a tuple. In Perl, the code looks like this:

sub identifier ( $str ) {

if ( $str =~ /^([a-z_]\w*)/ ) {

my $matches = $1;

$str =~ s/^$matches\s*//;

return ( 1, $str, $matches );

} else {

return ( 0, $str, undef );

}

}

(In Perl, =~ /.../ is the regular expression matching syntax, and s/.../.../ is regular expression substitution.)

But what about a parser like symbol? It takes the string representing the symbol as an argument, so in the example, symbol( "=" ) should be the actual parser. What we need is that a call to symbol will return a function to do the parsing, like this:

sub symbol ( $lit_str ) {

my $gen = sub ( $str ) {

if ( $str =~ /^\s*$lit_str\s*/ ) {

my $matches = $lit_str;

$str =~ s/^\s*$lit_str\s*//;

return ( 1, $str, $matches );

} else {

return ( 0, $str, undef );

}

};

return $gen;

}

This is of course not limited to string arguments, any argument of the outer function can be used inside the inner function. In particular, if a parser combinator takes parsers as arguments, like choice and maybe, then these parsers can be passed on to the inner function.

This is fine as far as it goes, but what about the labelled parsers? and what about the lists of parsers? Neither of these can be directly applied to a string, but neither is a function that can generate a function either. So to apply them to a string, we will need to get the parsers out of label-parser pair and the list. We do that using a helper function which I call apply, and which in Perl looks like

sub apply ( $p, $str ) {

if ( ref($p) eq 'CODE' ) {

return $p->($str);

} elsif ( ref($p) eq 'ARRAY' ) {

return sequence($p)->($str);

} elsif ( ref($p) eq 'HASH' ) {

return retag($p,$str);

}

}

(The syntax $p->($str) applies the anonymous function referenced by $p to its arguments.)

This function checks the type of $p using the ref built-in: it can either be code (i.e. a subroutine), an array or a hash. If it’s subroutine it’s applied directly to the string, otherwise it calls sequence or retag.

sub sequence ( $plst ) {

my $gen = sub ( $str ) {

my $f = sub {

my ( $acc, $p ) = @_;

my ( $st1, $str1, $matches ) = @{$acc};

my ( $st2, $str2, $ms ) = do {

apply($p,$str1);

};

if ( $st2 * $st1 == 0 ) {

return [ 0, $str1, [] ];

} else {

return [ 1, $str2, [ @{$matches}, $ms ] ];

}

};

my ($status, $str, $matches ) = @{

foldl( $f, [ 1, $str, [] ], $plst )

};

if ( $status == 0 ) {

return ( 0, $str, [] );

} else {

return ( 1, $str, $matches );

}

};

return $gen;

}

The foldl function is my Perl version of the left-to-right reduction in Haskell or reduce in Raku.

What retag does is taking the parser from the label pair (which is a single-element hash), apply it to the string, and label the resulting matches with the label of the parser:

sub retag ($p, $str) {

my %hp = %{$p};

my ( $k, $pp ) = each %hp;

my ( $status, $str2, $mms ) = $pp->($str);

my $matches = { $k => $mms };

return ( $status, $str2, $matches );

}

(The syntax %{$p} is dereferencing, a bit like the * prefix in C.)

Here is a simple example of how to use the list-based parser combinators.

my $str = " Hello, brave new world!";

my $str_parser = sequence [

whiteSpace,

word,

comma,

{Adjectives => word},

{Adword,

{Noun => word},

symbol "!"

];

my $res = apply( $str_parser, $str);

Implementation in a language with algebraic data types

All of the above is fine in a dynamically typed language, but in a statically typed language, the list can’t contain a function and a hash and another list, as they all have different types. Also, only testing if an entry of the list is code, hash or list is rather weak, as it does not guarantee that the code is an actual parser. So let’s see what it looks like in Haskell and Raku. list-based parser combinators In Haskell, we start (of course) by defining a few types:

-- The list-based combinator

data LComb =

Seq [LComb]

| Comb (String -> MTup String)

| Tag String LComb

-- The match, i.e. the bit of the string the parser matches

data Match =

Match String

| TaggedMatches String [Match]

| UndefinedMatch deriving (Eq,Show)

-- The tuple returned by the parser

newtype MTup s = MTup (Status, s, Matches) deriving (Show)

-- some aliases

type Matches = [Match]

type Status = Integer

(In Haskell, data and newtype define a new algebraic datatype; type defines an alias for an existing type.)

So our list of parsers will be a list of LComb, and this can be a parser, sequence of parsers or tagged pair. Because the tag eventually is used to label the matched string, the Match type also has a tagged variant. In principle, the return type of the parser could just be a tuple, but I define the MTup polymorphic type so I can make it an instance of a type class later on, e.g. to make it a monad.

With these types we can define our parser combinators and the apply and sequence functions. Here is the symbol parser. Many of the parsers in the library are implemented using Perl-Compatible Regular Expressions (Text.Regex.PCRE), because what else can you expect of a lamdacamel.

symbol :: String -> LComb

symbol lit_str =

Comb $ \str -> let

status=0

(b,m,str') =

str =~ ("^\\s*"++lit_str++"\\s*") :: (String,String,String)

in

if m/=""

then

MTup (1,str', [Match lit_str])

else

MTup (0,str, [UndefinedMatch])

(The $ behaves like an opening parenthesis that does not need a closing parenthesis; ++ is the list concatenation operator, in Haskell strings are lists of characters.)

The apply function pattern matches against the type alternatives for LComb. Because of the pattern matching there is not need for an untag function. It is clear from this implementation that we can write a sequence of parsers both as Seq [...] or sequence [...].

apply :: LComb -> String -> MTup String

apply p str = case p of

Comb p' -> p' str

Seq p' -> let

Comb p'' = sequence p'

in

p'' str

Tag k pp -> let

MTup (status, str2, mms) = apply pp str

matches = [TaggedMatches k mms]

in

MTup (status, str2, matches)

Apart from the static typing, the sequence function is very close to the Perl version. That is of course because I wrote the Perl code in a functional style.

sequence :: [LComb] -> LComb

sequence pseq =

Comb $ \str -> let

f acc p = let

MTup (status1,str1,matches) = acc

MTup (status2,str2,ms) = apply p str1

in

if (status2*status1==0)

then

MTup (0,str1,emptyMatches)

else

MTup (1,str2,(matches++ms))

MTup (status, str', matches') =

foldl f (MTup (1,str,emptyMatches)) pseq

in

if status == 0 then

MTup (0,str',emptyMatches)

else

MTup (1,str',matches')

In Raku, I use roles as algebraic datatypes as explained in my previous post. Essentially, each alternative of a sum types mixes in an empty role which is only used to name the type; product types are just roles with some attributes that are declared in the role’s parameter list.

# The list-based combinator type

role LComb {}

role Seq[LComb @combs] does LComb {

has LComb @.combs = @combs;

}

role Comb[Sub $comb] does LComb {

has Sub $.comb = $comb;

}

role Tag[Str $tag, LComb $comb] does LComb {

has Str $.tag = $tag;

has LComb $.comb = $comb;

}

# The matches

role Matches {}

role Match[Str $str] does Matches {

has Str $.match=$str;

}

role TaggedMatch[Str $tag, Matches @ms] does Matches {

has Str $.tag = $tag;

has Matches @.matches = @ms;

}

role UndefinedMatch does Matches {}

# The tuple returned by the parser

role MTup[Int $st, Str $rest, Matches @ms] {

has Int $.status = $st;

has Str $.rest = $rest;

has Matches @.matches = @ms;

}

The way the Raku regular expressions are used in this implementation of symbol is closer to the Haskell version than the Perl 5 version. But the main difference with the Perl 5 version is that the combinator and the return tuple are statically typed. The function undef-match is a convenience to return an array with an undefined match.

sub symbol (Str $lit_str --> LComb) {

my $lit_str_ = $lit_str;

Comb[ sub (Str $str --> MTup) {

if (

$str ~~ m/^\s*$lit_str_\s* $<r> = [.*]/

) {

my $matches=Array[Matches](Match[$lit_str_].new);

my $str_ = ~$<r>;

MTup[1, $str_, $matches].new;

} else {

MTup[0, $str, undef-match].new;

}

}

].new;

}

As explained in my previous post, we use Raku’s multi subs for pattern matching on the types. In Haskell this is also possible, and the definition of apply can be rewritten as:

apply (Comb p') str = p' str

apply (Seq p') str = apply (sequence p') str

apply (Tag k pp) str = let

MTup (status, str2, mms) = apply pp str

matches = [TaggedMatches k mms]

in

MTup (status, str2, matches)

The Raku version of apply is quite close to this Haskell version. For convenience, I use a function unmtup to unpack the MTup.

multi sub apply(Comb[ Sub ] $p, Str $str --> MTup) {

($p.comb)($str);

}

multi sub apply(Seq[ Array ] $ps, Str $str --> MTup) {

apply( sequence( $ps.combs), $str);

}

multi sub apply(Tag[ Str, LComb ] $t, Str $str --> MTup) {

my MTup $res = apply($t.comb,$str);

my ($status, $str2, @mms) = unmtup($res);

my Matches @matches = ( TaggedMatch[$t.tag, @mms].new );

MTup[$status, $str2, @matches].new;

}

Finally, the sequence code in Raku. It follows closely the structure of the Perl 5 and Haskell versions. Raku’s reduce is equivalent to Haskell’s foldl.

sub sequence (LComb @combs --> LComb) {

Comb[

sub (Str $str --> MTup) {

my Sub $f = sub ( MTup $acc, LComb $p --> MTup) {

my ($st1, $str1, $ms1) = unmtup($acc);

my MTup $res = apply($p,$str1);

my ($st2, $str2, $ms2) = unmtup($res);

if ($st2*$st1==0) {

return MTup[0,$str1,empty-match].new;

} else {

return MTup[1,$str2,

Array[Matches].new(|$ms1,|$ms2) ].new;

}

}

my MTup $res =

reduce $f, MTup[1,$str,empty-match].new,|@combs;

my ($status, $rest, $matches) = unmtup($res);

if ($status == 0) {

MTup[0,$rest,empty-match].new;

} else {

MTup[1,$rest,$matches].new;

}

}

].new;

}

There is still a minor issue with this definition of sequence: Because of the signature, we can’t write

sequence(p1, p2, ...)

Instead, we would have to write

sequence(Array[LComb].new(p1, p2, ...))

which is a bit tedious. So I rename sequence to sequence_ and wrap it in a new function sequence which has a ‘slurpy’ argument (i.e. it is variadic) like this:

sub sequence (*@ps) is export {

sequence_( Array[LComb](@ps) );

}

I do the same for all combinators that take a list of combinators as argument. If you wanted to type check the arguments of the wrapper function, you could do this with a where clause:

sub choice (*@ps where { .all ~~ LComb} ) is export {

choice_( Array[LComb](@ps));

}

The type constructor based tagging (Tag label parser) is nice in Haskell but in Raku it would look like Tag[label, parser].new which I don’t like. Therefore, I wrap the constructor in a tag function so I can write tag(label, parser).

An example of typical usage

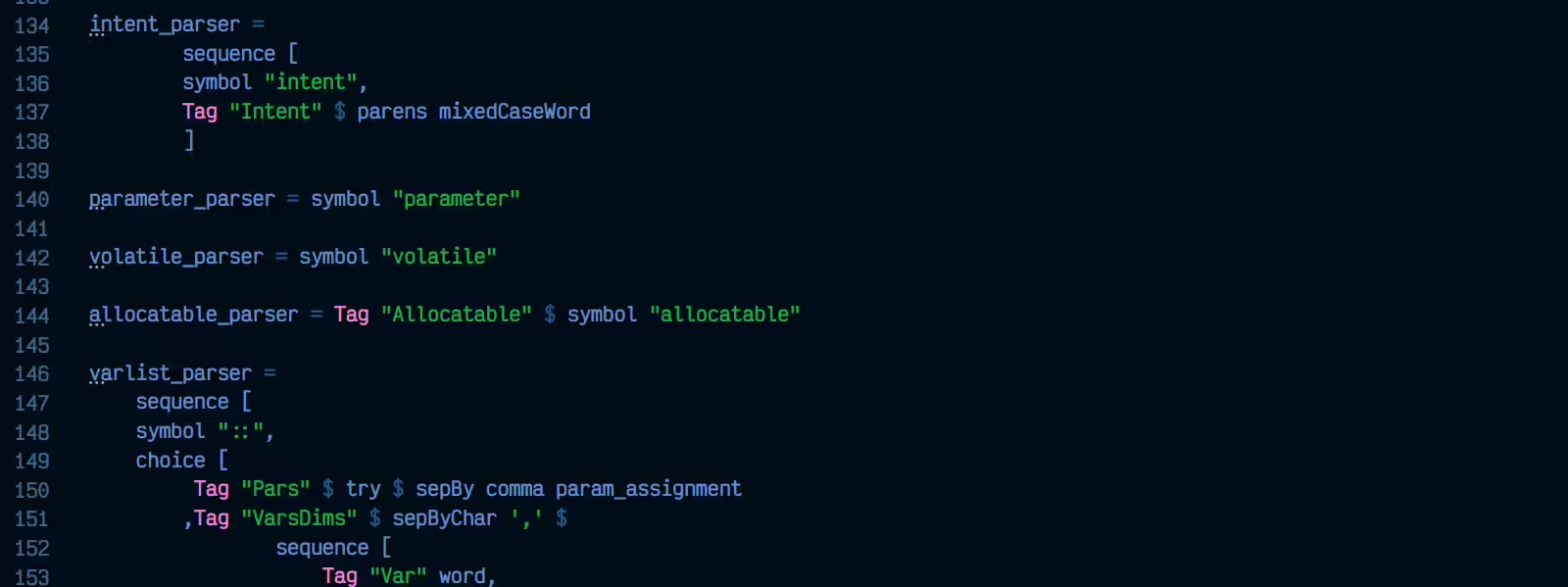

As an example, we can construct the following parser for a part of a Fortran 90-style variable declaration, apply it to the given string and get the parse tree:

my \type_parser =

sequence(

tag( "Type", word),

maybe( parens(

choice(

tag( "Kind" ,natural),

sequence(

symbol( "kind"),

symbol( "="),

tag( "Kind", natural)

)

)

))

);

my \type_str = "integer(kind=8), ";

my (\tpst, \tpstr, \tpms) = unmtup apply( type_parser, type_str);

say getParseTree(tpms);

(In Raku, variables declared with a \ are sigil-less )

For reference, here is the Haskell code:

type_parser =

sequence [

Tag "Type" word,

maybe $ parens $

choice [

Tag "Kind" natural,

sequence [

symbol "kind",

symbol "=",

(Tag "Kind" natural)

]

]

]

type_str = "integer(kind=8), "

main :: IO ()

main = do

let

MTup (tpst,tpstr,tpms) = apply type_parser type_str

print $ getParseTree tpms

(If you wonder about the strange signature of main, the do keyword or the let without an in, the answers are here. Or you could take my free online course.)

As is clear from this example, in both languages, list-based parser combinators provide a clean and highly composable way of constructing powerful and complex parsers. It is also quite easy to extend the library with additional parsers. I think this is a nice practical application of algebraic data types in particular and functional programming in general. You can find both the Haskell code and the Raku code in my repo.